A few weeks ago I led a session at the annual Enhancing Quality Staff conference, which is aimed at library staff members from around the Twin Cities who are not formally “librarians”. I’ve found the participants at this conference uniquely willing to engage in dialogue with me and with one another, so it’s a really special opportunity to try new approaches and cover new topics. This year, I presented a not-new topic in a new-ish format. Participants asked for slides, but those alone don’t cover the full breadth of the discussion – so here’s an attempt at that.

As always, I am a lawyer, but I’m not -your- lawyer, and this is not legal advice. Even more than usual, this is not legal advice. This is TOTALLY BIASED ADVOCACY.

What does institutional “compliance” mean to you? In many institutional/organizational settings, a “compliance” officer is someone who is responsible for making sure the organization complies with all applicable rules, regulations, and policies. The idea of compliance is pretty closely tied to the idea of risk reduction; compliance officers try to make sure the organization doesn’t run the risk of violating any applicable rules.

For example, at the University of Minnesota, the Compliance Office tries to make sure people are following laws and regulations around food safety, research ethics, student finances, travel and procurement regulations… and copyright. But unlike some other areas of law and regulation, there are a lot of judgment calls and grey areas in copyright. On possible approach to risk management around copyright is to try to ensure library users never do anything remotely risky or unclear. But I advocate for a different approach.

“Really??? Just letting people -do- stuff? Isn’t that…”

Okay, so first, a basic legal principle:

We don’t try to make sure our library users are following the law in a lot of other areas: for example, most libraries tolerate (or even embrace) a wide variety of approaches to personal interactions among users in our spaces. Obviously, there are some times when law or ethics may compel you intervene in the actions of another – for example, most library staff members would intervene (or might even be legally compelled to intervene) if a parent or guardian became physically abusive with a child in one of our libraries. But much of the time, it’s a -bad- idea to try to control other people’s behavior. It can -create- liability where none would otherwise exist. For example: many libraries might have a policy that states that only certain staff members can or should intervene in a physical altercation between adults in the library – both for staff safety, and to limit organizational liability.

So, what am I saying about copyright, here?

ENCOURAGE THAT???

That doesn’t just sound like staying out of a situation where a staff member might get hurt, or that might expose the organization to liability. That sounds…

That sounds…

That sounds…

Okay. You want to talk ethics?

“IV. We respect intellectual property rights and advocate balance between the interests of information users and rights holders.”

ALA Code of Ethics

http://www.ala.org/advocacy/proethics/codeofethics/codeethics

Is a teacher reading a book aloud to her class “respecting” copyright? What does it mean to “respect” copyrights?

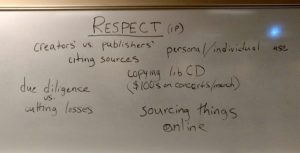

(At this point in the EQS session, we broke into small groups, to discuss the question. The following photo shows the wide variety of things people talked about in their small groups:)

The discussion was wide-ranging. Groups reported back that they had discussed:

- whose rights are we respecting? Creators’, or publishers’?

- citing sources

- personal/individual use

- sourcing things online

- copying library CDs when you have spent $100s on tickets and artist merchandise

- due diligence vs cutting losses (i.e., how much resources to devote to things like rights clearance, especially of materials where no final answer can ever be found?)

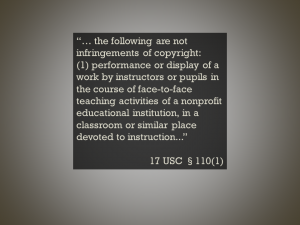

Obviously, a crew of deep, considerate, and critical thinkers. But let’s go back to the teacher reading to students example. Is she respecting copyrights if she reads to them without payment or permission?

Or would she be DISrespecting copyright, if she paid or asked permission – since there’s an explicit provision in the law authorizing nonprofit in-class performance or display?

What about other exceptions that explicitly authorize certain kinds of uses? Is it “respecting” copyright to seek permission or pay to do things that are authorized by law? Lots of people don’t know about the provisions that explicitly authorize certain uses by religious groups, or at horticultural fairs. (17 USC § 110(3) and (6), respectively!)

Is it “respecting” copyright to try to get permission for use of public domain materials?

Is it “respecting” copyright to try to hide that something is in the public domain, in order to tell people they need to seek your permission, or pay you to use it?

And what about fair use? Fair use is a flexible area of law – but it can also be characterized as uncertain.

If we want to “respect” copyright law, can we do so by relying on that squiggly fair use? Courts have said that copying from unpublished memoirs in a newspaper was NOT fair use, but copying from unpublished letters and journal entries for a biography was fair use. Sampling a single note in a commercial recording was NOT fair use, but 2 Live Crew commercially releasing their own version of Roy Orbison’s “Pretty Woman” against the express wishes of the Orbison estate was fair use.

Well, however squiggly it is, fair use is part of copyright law. And the law says that fair use is “not an infringement of copyright.” There are also some other pieces of the ALA Code of Ethics that might be worth a visit, here.

VI. We do not advance private interests at the expense of library users, colleagues, or our employing institutions.”

ALA Code of Ethics

http://www.ala.org/advocacy/proethics/codeofethics/codeethics

Copyright law should not expand the rights of copyright holders without sufficiently considering or benefitting the public interest. When the balance between rights holders and information users needs to be restored, librarians should engage with rights holders and legislators and advocate on behalf of their users and user rights.”

Copyright: An Interpretation of the Code of Ethics

Adopted by ALA Council on July 1, 2014

http://www.ala.org/advocacy/proethics/copyright

If we decide that fair use is too squiggly for us to handle, are we putting a private interest ahead of that of our users? Are we abdicating our role as advocates for the public interest in copyright?

Respecting the law, and complying with it, may sometimes involve not seeking permission, not seeking to pay – and even, sometimes, pushing on where the “boundaries” of squiggly fair use are perceived to be. Respecting copyright by making use of the -exceptions- to the ownership rights it creates can produce great public benefit.

The law already recognizes the public’s interest around copyright in a lot of ways (as in the exceptions outlined above.) There are also exceptions specifically for libraries, in 17 USC § 108. We can do a lot, if we stick to those!

But the provisions of section 108 are not the only copyright exceptions applicable to libraries, and we can do even more things, if we make use of all the public-interest provisions of the law.

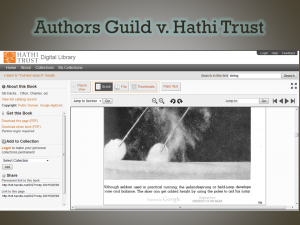

The Hathi Trust Digital Library (which involves many different partner organizations, but for which the University of Michigan bears primary organizational responsibility), took on a variety of projects to build on the books scanned via the Google Books project. Hathi has invested more in researching the public domain status of the works, done more to make them accessible to users with print disabilities, and done more to make them searchable and usable for researchers. They did all this knowing that others disagreed on whether their activities were fair use, and knowing they would likely have to go to court to defend their actions. But when they did go to court, the judges agreed with them.

I cannot imagine a definition of fair use that would not encompass the transformative uses made by Defendants.”- AG v. Hathi District court opinion

Now we -all- know more about what kinds of uses are fair uses.

But aren’t ©OPS Good Sometimes?

I confess, when I first met people who wanted me to help them police and control their library users around copyright, I couldn’t understand it. Most of the folks asking for help along those lines didn’t seem like power-tripping control freaks. Eventually, I realized they really did have a deeply service-oriented goal.

At least some of them were concerned with -preventing their users from getting into legal trouble-. On the other hand, some of them had a different orientation to communicating about copyright with users.

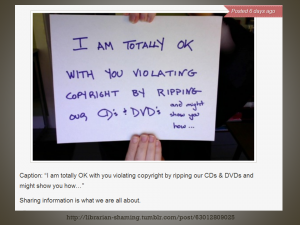

This attitude also bugs me a little – not just the encouragement to break the law – but much more so, the absolute failure to recognize that library users may be legally allowed to do these things. This person actually has the same misunderstanding of copyright as those who want to tell users “No” a million times, just a different follow-on action. Whereas I can think of a close-to-infinite list of at least plausibly fair uses: ripping in service of a use covered by the Classroom Use Exemption; ripping to make a mashup song; ripping to make a remix video; ripping for computational analysis…

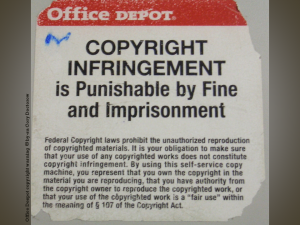

But these ideas that copyright has a clear right-and-wrong are pretty sticky. A lot of people feel that even legally permitted copying is a little bit “wrong” most of the time. And just learning more about copyright doesn’t always shift those beliefs. The way that organizations often communicate about copyright to their constituents may reinforce that feeling that copying is a “wrong” action.

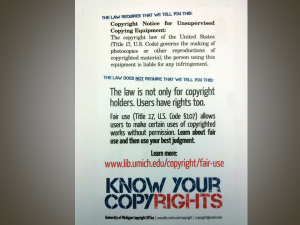

What might a library communication that’s not aimed at “compliance” – that admits that “compliance” is a fraught question in relation to a law that both outlines rights for owners -and- exceptions to all of those rights – look like?

An underlying consideration that I think is essential to considering how much effort libraries should expend towards “compliance” with copyright laws: users who have their own homes to go to, with their own technologies to play around with, and their own internet connections to send and receive through, get to make their own decisions about how they use any materials they check out of our libraries. We can help them to make informed choices about their actions through outreach and education programs, but ultimately, placing “compliance”-oriented limits on what can be done in the library, is just limiting in-library users.

Or, in an alternate view, is…

This kid was always going to be able to make his own cover-song videos and post them online, and reap the benefits of that, because he and his mom had the necessary tools & technologies at home.

But do you want your library to be the place that told these kids they couldn’t make an original song and video about their favorite snack foods, and reap the benefits of -their- subsequent popularity, because trademark law might not permit it?

Policewoman: Talk to the hand CC by-nc-nd Tom Fassbender

Hands in water: Washing hands CC BY-NC-ND SCA Svenska Cellulosa Aktiebolaget

Cat: Sneaking cat CC BY Hans Pama

Macaque: Sneaky beggar CC by-nd Kevin Botto

Shady toddler: Sneaky Eyes CC by-nd Big D2112

Teacher: Reading Aloud to Children CC by-nc-sa Judy Baxter/OldShoeWoman

Jello: Under the Sea Jell-O Mold CC by Carol at puresugar.net

Office Depot copier warning photo: Office Despot copyright warning CC by-sa Cory Doctorow

Digitization: Working on old photos CC by-nc-nd Vermegrigio