You found something really cool in an online archive! You think it’s in the public domain and you can use it, but the archive page says to contact the archive for information about copyright, so you do. And then no one will actually tell you whether it is or isn’t in the public domain, or anything useful at all! SO ANNOYING! Clearly, this is intentional obfuscation!

It really isn’t – in fact, in my experience, people who work in libraries and archives tend to be highly committed to meeting users’ needs – but I totally understand why people may feel this way. You’re encountering a confluence of complicating factors, and they’re not usually explained very clearly. (As usual, the following is mostly US-centric, though I’m sure some of these factors also exist elsewhere.)

First, there’s the whole “legal advice” issue. I am a lawyer, but I’m not -your- lawyer – so I can give general information about how the law works, but not specific advice on what you are or are not allowed to do. This is part of the rules of professional responsibility for lawyers, and violating these rules could get me disbarred. For people who are -not- lawyers, like most library and archive staff members, providing specific advice can put them on the hook as committing “unauthorized practice of law” (which carries different penalties in different states.)

These are deeply entrenched rules and norms – the likelihood that someone will actually complain about it if a lawyer provides advice to someone who is not their client is low. The likelihood that someone will complain if a non-lawyer library staff member provides advice is probably even lower. But the possibility is there, and it does happen from time to time, so people have some legitimate nervousness about that, and general rules of professional practice guide against providing specific info.

The “legal advice” issue can be solved by hiring your own attorney. They would -definitely- be allowed to give you legal advice about risks and benefits of particular plans or approaches. (But of course, that would be costly. My cynical side sees the rules and laws about who can provide advice as, at least partly, motivated by a desire to generate business for lawyers. Unfortunate, but a piece of the puzzle.)

Second, libraries and archives as institutions have long taken a -very- hands-off approach to evaluating the ownership status of items in our collections. We often have very incomplete information about these items (unlike art museums, which due to the different natures of their collections, usually have more detailed provenance information about individual items). Our institutional lawyers can be very uncomfortable with the idea of us providing information with legal implications to members of the public (due to the rules described above, and also possible liability if we tell someone there is no rights holder, but we’re wrong.) On top of that, there has been a tradition in archives to require permission -from the archive- for use of archival materials, even though that does not map directly onto how the law works.

Most of us in libraries and archives are, to varying degrees, trying to move -away- from that hands-off, “you’re on your own” approach to sharing information with the public, and on untangling archival traditions from legal details. A joint project of US and European organizations has produced a human- and machine-readable set of 12 basic rights descriptors that have great potential for standardizing public info. But it can be hard to figure out which one to apply!

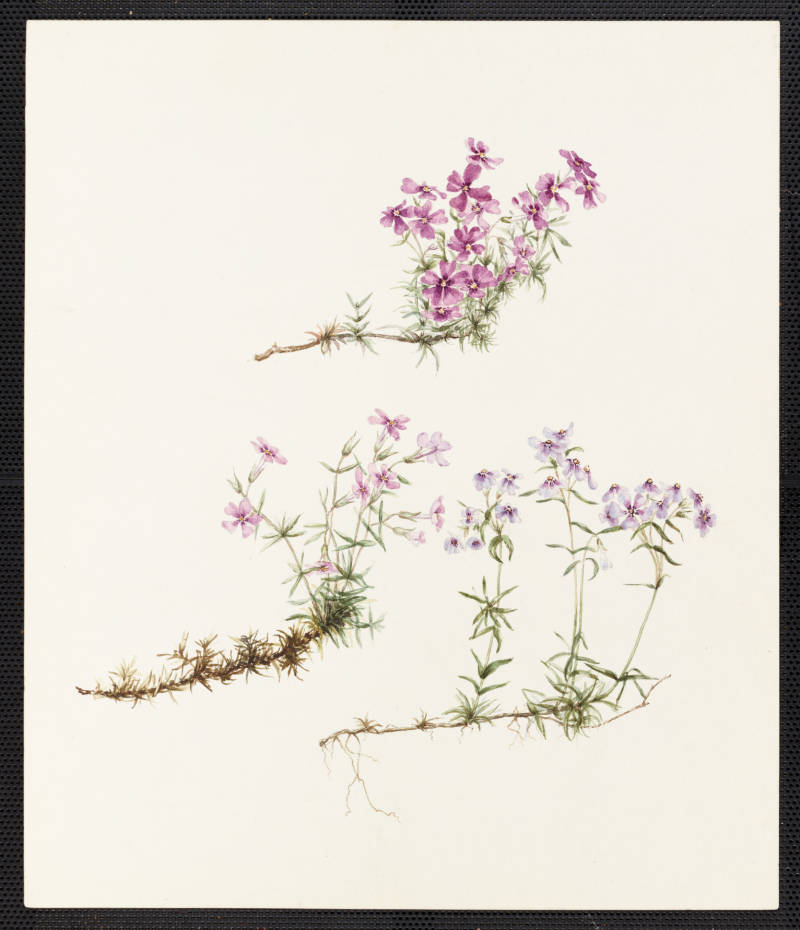

A team of folks at the UMN Libraries have been working heavily the last few months to add labels to our digital collections that provide more information about what we know about the copyright status of collection items. (You can see one example of what the end result looks like at the bottom of the page for this painting of Phlox Subulata, part of the Agnes Williams Collection of wildflower paintings from Andersen Horticultural Library.)

Which brings us to a third piece of this puzzle: it is often difficult to tell if something is in the public domain – and those determinations may be country-specific. The rights label we’ve attached to Agnes Williams’ paintings is “No Copyright – US” – this happens to be a fairly straightforward determination because these works were unpublished, and we know that Agnes died more than 70 years ago. (Note that in most countries, this “life of the author + 70” years term applies to most works – but in the US, it only applies to unpublished works, and only from certain time periods.) For a brief illustration of the complexity of this review process under US law, check out the intro workflow co-produced by the Minnesota Digital Library & UMN Libraries (and we don’t always have the info needed to answer even just these basic questions!)

The 12 standardized Rights Statements are very helpful here: the public display text is very clear that we haven’t assessed items under the laws of other countries. If you click through to the full text of the “No Copyright-US” label , you’ll also see that it contains a lot of disclaimer language: this is our best guess, we make no guarantees our assessment is correct. Those limitations have helped to make institutional lawyers more comfortable with sharing this kind of information with the public.

In addition to trying to clear up copyright communications for items that may -not- have a copyright owner, some libraries and archives are expanding further into making rights more understandable and making our collections more useable. One way we can help with this is to identify items where there -is- a knowable existing rightsholder – and ask them to pre-approve public use! The YMCA has authorized UMN’s Kautz Family YMCA Archives to share many items that do have a copyright, and in many cases has authorized the application of a Creative Commons license permitting non-commercial use with attribution.

Worries about providing legal advice, challenges of changing organizational culture, and complexity of legal facts aren’t the -only- factors that contribute to institutional reluctance to be straightforward about copyright status. Obviously, specific instances of confusion may have many different contributing factors. But hopefully, this outline makes it a little clearer why things are not always so clear, here!