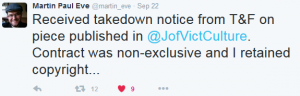

Saw this tweet yesterday, and was intrigued.

To unpack from Twitter’s 140-character limit, author Martin Paul Eve is saying that the publisher Taylor & Francis (“T&F”) has requested that one of his articles, originally published in the Journal of Victorian Studies (“@JofVictCulture”), be removed from some online site. In particular, “takedown notice” implies that Taylor & Francis claimed that they owned the copyright in the article, and based their request for removal on that supposed copyright ownership. But, Eve says, the contract he signed with Taylor & Francis was non-exclusive (i.e., he didn’t give T&F exclusive ownership of any rights), and he retained copyright ownership! So, Taylor & Francis may well not be the owners of the copyright in this work!

In my experience, sometimes when authors request to not transfer their copyright to a publisher, the publisher provides an “alternative” form contract that grants an -exclusive- license to a wide variety of rights. The end result of signing such a contract is almost the same as transferring the copyright, because the publisher is the only one authorized to exercise those rights. I have specifically seen such a contract from Taylor & Francis in the past (though I do not know if this is a current practice.)

But Eve is very well-informed about these issues, so I didn’t think he’d be tripped up by even that subtle a move. I followed up with him for more detail (and to make sure he’d be okay with me writing a blog post about the incident), and indeed he -did- receive the “exclusive rights” alternative contract from T&F, but before signing & returning, he edited it to remove the word “exclusive”!

I do not claim great expertise in non-U.S. law (and both Eve & the journal are located in the UK), but my overall impression of the contract as signed is that it could be -clearer- about control of specific rights, but it is 100% clear that Taylor & Francis do not own the copyright, and not at all clear that T&F has any exclusive rights to the article.

Unfortunately, the host of the specific copy of the article had already taken down the article by the time Eve received notice of the takedown – whether they will put it back up, or not, is yet to be seen. Eve does have some other open copies elsewhere online, and the T&F original is still accessible, so his work is still readable. But this could have come out very differently.

Important takeaways for authors

1. You can 100% negotiate your publication contracts.

A lot of authors feel uncomfortable asking publishers to change publication contracts. But many publishers are quite willing to be flexible – and many publishers have policies that are more friendly to authors even without negotiation! Authors can look up publishers at SHERPA/RoMEO (and click through to the publisher’s actual policies) to select outlets that accommodate their preferences in baseline practices. There are also times when an author would be actively interested in publishing with an outlet that does not have such friendly baseline policies. In that case, it rarely hurts to ask for changes.

In my experience, authors sometimes worry that an article will be un-accepted if they ask for changes to a publication agreement. I’ve never heard of that happening, though I have heard of publishers who absolutely will not accommodate author requests on this point. (In that case, the author faces the choice of agreeing to the publisher’s terms, or not having their article published. Even then, the publisher is usually happy to accept the article when the author does decide to agree to their terms.) What authors may not always realize is that – especially when it has already been reviewed and found acceptable – the publisher needs your article! So many of them are willing to negotiate.

2. KEEP COPIES OF YOUR CONTRACTS, ESPECIALLY IF YOU NEGOTIATE SPECIFIC TERMS

Publishers have few incentives to keep careful track of which authors they signed non-standard contracts with. If you believe you retained rights in a work, but have no record of the specific terms of your agreement, the publisher (and other parties) will likely assume that you agreed to their standard agreement. In Eve’s case, depending on the attitude of site hosting the paper, he might be able to invalidate T&F’s takedown request. But that is entirely dependent on the fact that he has a record of what he -actually- submitted to T&F.

Important takeaway for hosts of author-deposited copies of academic papers

If you want to claim the safe harbors of the DMCA, you don’t have a lot of wiggle room in how you respond to a takedown request. Under U.S. law, someone who submits a DMCA takedown request must swear that they have a good faith belief in their claim of copyright ownership/infringement – but the host who wants to stay within DMCA policy will probably need to take that at face value.

However, for hosts that are not relying on the DMCA to begin with (i.e., most library/institutional repository hosts, and many disciplinary repository hosts), there is no need to follow the DMCA’s steps in response to a takedown request. (Also, not all “takedown requests” are DMCA takedown requests, but that’s an are for another blog post or three.) Since we know quite well that many academic authors, like Eve, are savvy enough to retain their rights, it is perfectly reasonable to respond to a takedown request from an academic publisher with a request that they provide evidence of their rights ownership. I know some academically-hosted repositories have done so in the past.

Important takeaway for academics in general

Academic publishers do have incentives to keep their originals accessible. But third party article hosting services that are not themselves either publishers or directly run by academic institutions or organizations have little incentive to fight to preserve access to any individual article on their site. When Elsevier sent takedown requests to Academia.edu, Academia.edu took down the articles – because that is the rational response of a for-profit company whose business plans are primarily oriented to monetizing the social graphs of academics. (Note that -many- of those takedown were about articles where Elsevier absolutely -did- own the copyrights.)

To preserve open versions of content originally published in closed venues, and to support authors who do the work of retaining their rights, there -must- continue to be copies hosted on servers -run by academics-; either institutions, or disciplinary organizations. These are the organizational actors that have serious incentives to do active advocacy in the service of long-term preservation and access.