I’m calling this “Good Practices” rather than “Best Practices”, because hey, there might be better ones!

Images punch up presentation slides, it’s true. In fact, some of the most effective presentations I’ve ever seen have relied heavily or even exclusively on image-based slides. However, I very often see images used something like this:

The image is striking, and I definitely want to hear what a speaker has to say about it! But I’m distracted by that URL on the bottom – what’s it doing there?

The URL is because of copyright! Or citation! Or something!

If the presenter included the URL in an effort to comply with copyright restrictions, they’re pretty far off the mark. Often, presenters consider their use of an image to be fair use – and often they think that giving proper credit is part of fair use. This is a misconception: no URL, citation, or attribution is required under fair use – and if the use is not fair, no URL, citation, or attribution will make it so.

This particular image happens to be in the public domain – so a presenter using this image on a slide would not have to wonder if their use was fair. But neither would the presenter have to provide a URL, citation, or attribution. No one owns public domain documents; anyone can do anything they want to with them!

Certainly giving credit and/or citing sources is an important part of many forms of discourse – but if the presenter was trying to give me information about the source of

the image, the URL (especially such a long one) gives me almost no useful information. A traditional citation or a brief caption would be more informative for viewers than a URL. But including any textual information directly on the slide can be a big distraction: a list of citations, including URLs, as part of a bibliography or “image index” slide towards the end of the presentation might be a useful alternative in such situations.

I’d also suggest that, when the mode of discourse doesn’t call for it, or when an image is so iconic that everyone knows where it came from in the first place, providing a citation on a presentation slide looks a little silly. It’s not a moral failure to skip providing attribution. In fact, it’s so much not a moral failure that United States copyright law almost never cares about attribution or citation.

But I’m using Creative Commons images – I have to include the URL!

Creative Commons resources are AWESOME! I love Creative Commons! (Happy Birthday, Creative Commons!) I’m sure I’ll talk a lot about Creative Commons on this blog, including posts in the future about what CC is, how you can use stuff that’s available under CC, and making your own stuff available. However, the issues I’ve seen on presentation slides are from people who already know a lot of the basics, but are also a little confused.

It’s true you must provide attribution anytime you use something that’s CC-licensed (except for CC0-licensed works.) However – URLs are not sufficient to satisfy Creative Commons attributions requirements!

A lot of folks get their CC-licensed images from Flickr, and Flickr’s Community Guidelines do ask you to link back to the original image on their site. But the Community Guidelines aren’t exactly a legally binding document (especially for people who are not registered users), so it’s not a legal requirement to link back to the original. It’s certainly good practice to link back when you can, but in offline media, sometimes you just can’t.

What you can do, and what is actually required under the Creative Commons licenses, is provide full attribution, either on the slide itself, or in a list of images on a separate slide towards the end of your presentation.

At minimum, proper Creative Commons attribution should include:

- the name or user ID of the creator

- the title of the work, if any

- the Creative Commons license under which the original work is available

- a reproduction of any copyright notices the creator included

- if you’ve made a derivative work, an identification that your work is derivative

Here are some examples of Creative Commons attributions that meet these standards:

On presentation slides:

On paper and PDF copies of a poster:

You may note that I often downplay the attribution by using small font sizes and lower-contrast text colors (though readable for most audience members.) This is because extraneous text on the slide is distracting to viewers. Sometimes a list of image credits towards the end of the presentation really is the most sensible way to provide attributions. When displaying my own images, public domain images, or even sometimes images under fair use, I usually credit them verbally, if at all.

Tips and tricks to help with appropriate Creative Commons attribution:

- Save images with file names that include the appropriate information. Examples from my image folder: “GeneticsExhibitSanJoseTech-ccbync-ThomasHawk.jpg” and “CourseReaders-byncnd-SteelWool.jpg”

- Download some Creative Commons icons, or get the CC Icons font

- Use an attribution helper script (this one requires the Greasemonkey plugin, and I haven’t yet seen any that create entirely ideal attributions.)

Creative Commons images that appear in the examples in this post:

UPDATE: Creative Commons has a great post on their Wiki about attribution practices, including in videos, etc.: https://wiki.creativecommons.org/wiki/Best_practices_for_attribution

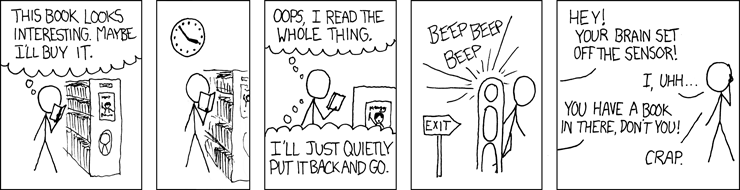

Being a lawyerbrarian, I often have conversations with people about how the law works. Fairly often, those conversations are frustrating, discouraging, or downright disheartening for all involved. Here’s a hypothetical rendering of one such conversation:

Being a lawyerbrarian, I often have conversations with people about how the law works. Fairly often, those conversations are frustrating, discouraging, or downright disheartening for all involved. Here’s a hypothetical rendering of one such conversation: