©Libn, circa 1976

Nancy Sims, Lawyerbrarian at large

The lawsuit against Georgia State University brought by a number of academic publishers (including Cambridge, Oxford, and Sage) and funded by the ostensibly non-profit Copyright Clearance Center proceeds to trial on Monday morning. At issue is the widespread re-use and sharing of academic content among faculty, staff, and students at a large university – sharing and re-use that is essential to the academic endeavor. It is quite devoutly to be hoped that Georgia State will win at trial, and that we will get a court opinion holding that many currently common practices of sharing and re-use in education are permitted as fair use.

However, it’s possible that Georgia State will not win, and recent documents filed by the publisher plaintiffs highlight just how bad the outcome could be in that event. The document in question is the publisher plaintiffs’ proposed injunction – the remedy they are asking the court to apply if they win. Among other restrictions on re-use and sharing, the publishers are asking the court to impose the 1976 Guidelines for Classroom Copying as the maximum standard for fair use on the Georgia State campus.

That the publishers would ask for this as a proposed injunction is surprising and disturbing. For a number of reasons applying the 1976 guidelines to educational use in 2011 is absolutely ridiculous!

It was much more difficult to make and share copies with colleagues and students in 1976 – but few people ever thought that copyright was an issue when doing so.

Well, if the court were to impose this injunction on Georgia State, you can bet that publishers would bring lawsuits against other universities, colleges, and educational institutions pointing to the Georgia State decision as precedent.

But even if the publishers don’t win in the Georgia State case (and goodness knows I hope they don’t) and this injunction is never granted, the simple fact that it was requested, by academic publishers, is a graphic indication that these particular publishers and the Copyright Clearance Center are in no way interested in fostering research, teaching, and scholarship. They’re interested in exercising maximal control over every bit of content they own, and squeezing money out of schools and users every single time we use, or share that content.

Most of the content published by academic publishers is produced by our own faculty and students – it is past time to commit to new models for distributing this content that don’t leave it in the hands of rent-seeking, for-profit businesses with no respect for academic values.

For a detailed analysis of the full request from the publishers, check out Duke’s Kevin Smith outlining “A Nightmare Scenario for Higher Education”. And Brandon Butler from the Association of Research Libraries has provided an insightful highlighting of what the publishers left out of the copy of the Guidelines that they submitted to the court.

*Because I am an attorney and bound by legal professional ethics requirements, I do not provide legal advice to people who are not my clients. I do often share information about how the law works, such as explaining the elements of a fair use analysis, without providing legal answers, such as whether a particular use is fair.

I got some great input, both here on the blog and elsewhere, on the Librarian’s Copyright Litany. Here’s a revised version.

![]()

The Librarian’s Copyright Litany

Remembering that copyright’s constitutional purpose is to stimulate creation for the benefit of the public; and recognizing that in its current formulation (and many possible future formulations) the public interest in copyright is not well-served; may we:

– Strive to meet the present and future needs of the communities we serve;

– Stand firmly and expansively in the areas where copyright law already recognizes public rights and interests; and

– Zealously promote a greater recognition of the public interest in copyright in our daily interactions with our users and other members of the public, through our own contract and licensing negotiations, and in legislative and judicial processes.

![]()

This post is about library budget cuts – specifically cuts that decimate our collections budgets. We all face them. They are heartbreaking. Ultimately, collections cuts (as with many other library budget cuts) ask us to select the least bad of an array of options that all cause serious harm to some or all of our user population.

Most decisions about which resources to cut are accomplished by (painfully, rigorously) considering a number of criteria: cost savings, how heavily the resource is used, whether it is used by central (for mission-critical and/or political values of “central”) portions of the user population, whether it is central to our institutional or organizational identity, whether there are alternative services, and a host of others. If it is not already part of your criteria for collections cuts, I’d like to suggest one more:

We all know we’re going to take criticism for whatever cuts we make – just about any service we currently provide is a favorite of someone, somewhere. When faced with the task of justifying decisions to a dedicated user of a recently-cut resource, wouldn’t “…and we also thought that the way the software prevents you from cutting-and-pasting the text was a pretty unreasonable restriction on your use” or “…and also, the fact that you’re not supposed to link to this resource from your course website, despite the fact that we’ve paid for your students to access it as individuals” lend another bit of weight to the discussion?

UPDATE: revised version now available

Exploring some exhortatory language to counter the message I encounter from many librarians that copyright is an area where our primary concern should be “compliance”. I don’t think this is a finished version – very much welcome your input/suggestions/feedback.

Inspired by Lessig’s “Certificate of Entitlement” to question copyright law (clearer copy) and Niebuhr’s “Serenity Prayer”.

The Librarian’s Copyright Litany

May we:

– Strive to meet and advocate for the needs, both present and future, of the communities we serve;

– Recognize that copyright law in its current formulation, and in the preferred future formulations of most content providers, primarily presents a barrier to meeting those needs – but stand firmly and expansively in those areas where the law already recognizes public rights; and

– Zealously promote all avenues towards a greater recognition of the public interest in copyright, including in the public consciousness through our daily interactions with our users, through our own contract negotiations, and in legislative and judicial processes.

Actually, one question I already have: should the title be a singular or plural possessive? I’ve already flip-flopped a couple times since starting the post…

Nothing in U.S. copyright law is straightforward, but the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) is a special source of confusion. One reason for the confusion is that several DMCA provisions are extremely technical with regard to both legal and technological details. Another reason for the confusion is that, while most people think of the DMCA as something like “the digital/internet copyright stuff”, the DMCA was actually a catch-all bill that included a number of revisions and additions to existing copyright laws, some of which had nothing to do with internet tech or digital formats at all. Herewith (how’s that for a lawyer word?), a brief overview of what-all is/was in the DMCA.

The Digital Millenium Copyright Act, (P.L. 105-304 – link retrieves full text of the bill) was passed on October 28, 1998. It was subtitled, “An Act To amend title 17, United States Code, to implement the World Intellectual Property Organization Copyright Treaty and Performances and Phonograms Treaty, and for other purposes.”

The act itself is made up of five “titles”, or sections. The Titles’ titles are, in order, “WIPO Treaties Implementation”, “Online Copyright Infringement Liability Limitation”, “Computer Maintenance or Repair Copyright Exemption”, “Miscellaneous Provisions”, and “Protection of Certain Original Designs”. Some provisions from Titles I-IV may be familiar to readers with more than a passing acquaintance with copyright law. Provisions from Title V are less likely to be familiar, unless you are an IP geek or participate in certain expensive hobbies.

The DMCA amended and added to existing copyright law in several different ways. It created several brand new sections of the copyright code (17 U.S.C. §§ 512, 1201-1205, 1301-1332; 28 U.S.C. § 4001) and made major changes to several other sections. All of these alterations were “part of the DMCA”, but you’ve probably only heard of a few of them.

The “big name” pieces of the DMCA are from Titles I and II: the “anticircumvention” provisions (codified at 17 U.S.C. § 1201), and the “notice-and-takedown” provisions (codified at 17 U.S.C. § 512). I plan separate “Delving into the DMCA” posts on each of them, because they are well-known for good reasons!

You are likely to have heard of the anticircumvention provisions partly because they create civil and criminal liability for many daily activities of our technology-driven lives (modifying hardware you rightfully own, taking clips of content from a DVD or Blu-Ray disc) and partly because there is a process of petitioning for exemptions to the restrictions that brings them back into the public eye every three years or so. You are likely to have heard of the notice-and-takedown provisions because, by insulating service providers from copyright liability for content users post, they’ve been key factors in the growth of user-generated web content (YouTube, Facebook, blogs – basically all of “Web 2.0”.)

Title I includes several technical provisions having to do with the rights of international copyright holders, amending various pieces of U.S. code to bring us into alignment with our treaty obligations. One piece restored the copyrights in some international works that had moved into the public domain – which may actually sound familiar, as the Supreme Court just granted cert on (agreed to review) the constitutionality of a very similar, slightly earlier law.

Title I also contained a provision (17 U.S.C. § 1202) that, more or less, makes it illegal to mess with the metadata on copyrightable works. There’s more to it than that, and it hasn’t been well hashed-out by courts – so it’s likely also a future blog post.

Title II was primarily concerned with the § 512 notice-and-takedown provisions. It also makes it clear that linking to infringing content, when there was no reason to know that linked content was infringing, the links themselves are not something service providers are liable for.

Title III updated a particular provision of the copyright code (17 U.S.C. § 117) that was enacted to deal with the ridiculous repercussions of one court’s immensely stupid early computer-copyright decision.

The “Miscellaneous Provisions” of Title IV are quite wide-ranging. Two large pieces have to do with perfomance rights in sound recordings for radio and online broadcasting. Another piece has to do with collective-bargaining rights of folks involved in big-studio movie production. Perhaps the most interesting piece to readers of this blog is the provision that updated 17 U.S.C. § 108 to give libraries the right to make digital preservation copies of materials from our collections – before the DMCA, we only had an exemption for making analog copies.

Title V, the one about “Protection of Certain Original Designs” actually had its own legislative title – the “Vessel Hull Design Protection Act”. That’s right, the DMCA has a section about boats. (Suddenly, these illustrations make slightly more sense, eh?)

The DMCA creates a copyright-like ownership right in designs for hulls of boats less than 200 feet long that “make the article attractive or distinctive in appearance.” It’s not an insignificant piece of legislation, either. Copyright is not supposed to protect useful objects – that’s supposed to be the realm of patent. But patent has a fairly high requirement for “novelty” and “nonobviousness” that most boat hull designs would never reach. This provision really blurs some lines between patent and copyright, and creates a whole new form of intellectual property for this very narrow field of design. For more info, check out this joint report from the U.S. Copyright Office and Patent & Trademark Office.

Anyway. There’s my brief overview of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. Hope you found it informative. If you still want to know more, the Wikipedia article is quite good; and this summary from the Copyright Office is techical, but readable (and was my main reference in writing this post.) Or you could go read the text of the legislation itself.

You may or may not have heard about the extensive saga that is George Lucas’ dispute with one of the costumers/prop makers from the original Star Wars series about the copyright in Stormtrooper costumes. The prop maker has been using the molds he used to make the original props for the movies to produce and sell new Stormtrooper costume pieces for the fan costume and memorabilia market. Lucas does not like this, and wants the prop maker to stop.

It’s an interesting story for copyright geeks, with some very technical wrinkles. Although the helmet designs did not originate with the prop maker, he made modifications and alterations to the design in the mold-making and casting process, so to some extent the designs are “original” to the prop maker. So who owns the design of the helmets as they came out of the mold? More fundamentally, there is a big issue as to whether a helmet is a “sculpture” (and hence copyrightable), or a utilitarian object (and hence, not ownable under UK law).

There are also some interesting international-law issues, and (although not directly applicable in the current instance of the lawsuit) some parallels to the works-for-hire/termination-of-transfers issues that are raging through the comic-book world lately (I’ll probably blog about that at some point, too. Comic book copyright issues are really cool!)

Technical copyright-geekery aside, this case points up some broader public interest issues in intellectual property and popular culture. Without suggesting that George Lucas, Lucasfilm (and a bajillion other entities) don’t/shouldn’t have any property-like interests in their creative works, Star Wars is a great example of a creative work that has taken on a lot of additional social meaning beyond Lucas’s contributions. The photos illustrating this post show just a few of the directions this property has been taken by the forces of human culture.

If Star Wars didn’t have this additional meaning, there wouldn’t be enough interest in Stormtrooper costumes for the prop maker to exploit! And although the cultural significance of Star Wars is certainly aided and abetted by the massive industrial content producer that is the Lucasarts empire, quite a bit of the social significance and meaning of Star Wars has only weak ties to Lucas’s properties, and/or represents tremendous creativity and meaning-building outside of formal authorship and ownership structures.

It’s worth considering that under the first U.S. copyright term, the copyright in Episode IV (the first Star Wars movie, released in 1977) would have expired in 2005. Of course, that’s not the term Episode IV was actually created or released under, and copyright law as formulated in the first U.S. copyright act would have no idea what to do with something like the Star Wars franchise. However, copyright law as formulated in early U.S. copyright acts would also have had very little conception that an individual’s personal interactions with contemporary content could rise to the level of infringement.

Whether you’re building a screen-accurate replica Star Wars costume for yourself (or your offspring) in your spare time or not, chances are there are elements of contemporary content with which you connect and interact on a very personal level. And since copyright ownership is so expansive, chances are many of those pieces of culture that are significant to you are legally owned by someone else, who has a legal right to stop you from doing some of the things you like to do with that content. Fair use is one part of the law that makes a little room for personal interactions with content. But since a lawsuit to establish whether a use is fair or not is very costly, most settled law around fair use reflects the interests of industrial content providers. Occasionally, industrial interests lose fair use cases anyway, often because a court has recognized a greater public interest – see Campbell v. Acuff-Rose (the “Pretty Woman” case), for example.

Judge Kozinski made some important observations in Mattel, Inc. v. MCA Records, Inc. (the “Barbie Girl” case): “Trademarks often fill in gaps in our vocabulary and add a contemporary flavor to our expressions. Once imbued with such expressive value, the trademark becomes a word in our language and assumes a role outside the bounds of trademark law.“ (see paragraph 9) Of course, trademark and copyright are not as similar as many people think, but the central point rings true across all intellectual property that affects culturally meaningful works – while the works are certainly products of their creators, their cultural significance is a product of larger, more public, more communal, cultural forces. Yet much of the time, the law does not recognize those public and personal forces as officially legitimate.

Expanded copyright protection may (may) have increased production of resource-intensive products like the Star Wars universe. But it also means that our culture does not legally belong to us. Something to keep in mind the next time someone starts talking about copyright “balancing” public and private interests.

(True confession: One main reason I started writing this post was to use action figure photos as illustrations. It got more reflective after I started writing.This also represents the first post on this blog where some images are being used under a fair use rationale, rather than Creative Commons licenses.)

Here’s a sneak preview:  It’s not 100% done – but we don’t expect it ever will be! Part of the overhaul was moving the site to a new, easier-to-update content management system. The other goals of the overhaul are to provide more up-to-date information in more easily understood formats. Consider this something of a public beta – we welcome your feedback and input!

It’s not 100% done – but we don’t expect it ever will be! Part of the overhaul was moving the site to a new, easier-to-update content management system. The other goals of the overhaul are to provide more up-to-date information in more easily understood formats. Consider this something of a public beta – we welcome your feedback and input!

And coming soon – copyright info videos!

Jong schaatsertje met val-kussen / Young skater with safety cushion, 1933. Nationaal Archief, Nederlands.

Jong schaatsertje met val-kussen / Young skater with safety cushion, 1933. Nationaal Archief, Nederlands.It’s a little cold lately, here in Minnesota in general, and in my office in particular. I understand that several other parts of the country are also a little chilly +/- snowy. In the interests of spreading thoughts, at least, of warmth, the topic of today’s “Joys of the Public Domain” post is…

SWEATERS! Woo!

(Click on any picture to go to the original full image page.)

Sweaters are useful pieces of clothing in many contexts. We (humanity in general) have apparently been knitting for at least three thousand years. (That link goes to the Wikipedia article on knitting. The one on sweaters cites no sources at all, though some of its unsubstantiated information is interesting or amusing.)

It’s amazing how far back some photos go:

The Swedish fishing family in the picture at left was photographed in 1863. The fisherman at right, in a sweater with a fairly intricate knit texture, posed for his portrait around 1900.

The Swedish fishing family in the picture at left was photographed in 1863. The fisherman at right, in a sweater with a fairly intricate knit texture, posed for his portrait around 1900.

Fisherman family, Grundsund, Sweden; Swedish National Heritage Board; ‘A Fisherman At Home’ by P.H. Emerson. National Media Museum (U.K.)

Maggie Jones, at left, was playing baseball in Cleveland in 1911 – a detailed texture is visible in her sweater in the full image. Russ Ford, at right, played for the New York Yankees in 1911. His team sweater has the letters “N” and “Y” knit right in.

Maggie Jones, at left, was playing baseball in Cleveland in 1911 – a detailed texture is visible in her sweater in the full image. Russ Ford, at right, played for the New York Yankees in 1911. His team sweater has the letters “N” and “Y” knit right in.

Maggie Jones of Cleveland, LoC.; Russ Ford, New York, AL, LoC.

I thought the following images were interesting comparisons of activities of kids of similar ages. The children at left are in school in Virginia in 1958; the children at right are working in Oregon – time unspecified, but (I’m guessing) probably in the 1910s-1930s. And all in interesting sweaters!

Navy Hill School, Library of Virginia; Two children with hops basket, Oregon State University Archives.

Some folks’ sweaters are an expression of personal style. The woman at left was photographed dancing in 1976. The man at right was photographed on a picnic at an unspecified time – I’d guess 1940s or 1950s from the car in the larger photo.

Some folks’ sweaters are an expression of personal style. The woman at left was photographed dancing in 1976. The man at right was photographed on a picnic at an unspecified time – I’d guess 1940s or 1950s from the car in the larger photo.

2nd Ave + 86 st. by James Jowers, George Eastman House Collection; Cape Verdean Picnic, Nantucket Historical Association.

Lots of folks think there are no recent works in the public domain; color photos can be a bit of a surprise. Here are some full-color photos of sweater-wearers in 1939, 1944, 1973, and 1974!

Girl with doll standing by fence, 1939, LoC; C&NWRR, towerman R.W. Mayberry of Elmhurst, Ill., at the Proviso yard, 1944, LoC; Neighborhood Children of the Neptune Road-Lovell Street Area, the Residential Community Closest to Logan Airport, 1973, U.S. Nat’l Archives; Two Youths and a Dog in Paterson, New Jersey, 1974, U.S. Nat’l Archives.

Possibly the complete apotheosis of sweater-ness is apparently 1950s Canadian curling teams.

I have immense respect for these women, whose (probably hand-made) sweaters feature curling stone intarsia (knit patterns/pictures.)

I have immense respect for these women, whose (probably hand-made) sweaters feature curling stone intarsia (knit patterns/pictures.)

Curling Women’s Champs, March 3, 1954, Galt Museum & Archives; Women’s Curling Champs, February 29, 1956, Galt Museum & Archives.

Several entire curling teams of the era rocked amazingly awesome sweaters. Check ’em out:

Elks Curling Champs, March 17, 1957, Women’s Curling Alberta Champs, January 26, 1955, Women’s Curling Bonspiel Champs, March 2, 1955. All from Galt Museum & Archives.

I just don’t think we could top that. Must be done!

“Joys of the Public Domain” is a recurring feature on this blog, celebrating works in the public domain that I have found and enjoyed. I hope that featuring them here will help expand folks’ ideas about the works in which we all share ownership!

A librarian colleague recently sent out an announcement about the UM Libraries’ copyright workshops to faculty in one of the departments she works with. One of the faculty members responded to my colleague by suggesting that such educational

opportunities would be more valuable for her, as a member of the faculty, if they were conducted by someone who “really knows about copyright, like an attorney.” This is not the first time I’ve had someone (almost always a faculty member) suggest librarians aren’t a “real” source of information about copyright.

This makes me angry – but not on my own behalf. I have a J.D. and an attorney license I can wave at people who are this hung up on credentials.

This makes me angry on behalf of my colleagues (MLS-accredited librarians and beyond), many of whom are far more qualified to discuss copyright with a faculty member than many attorneys. Here are some reasons why:

1. A lot of lawyers don’t know much about copyright

I got an email the other day from a classmate who took a course in copyright law with me asking if he could just copy images from other websites onto his blog, because you can just use things that are online, right? Dude (who shall remain nameless) is a practicing attorney. And very very wrong about a basic issue in copyright.

The standard law school curriculum never goes anywhere near copyright. Even “IP overview” classes usually spend a lot more time on patent and trademark than on copyright, although that’s changing at many schools. Almost all attorneys have a baseline knowledge in contract, property, criminal law, and other standard subjects. But they do not have such knowledge of copyright. And copyright is a pretty complicated area of law. It’s in the professional ethics code (see CA ethics code) that attorneys can get themselves up to speed on unfamiliar areas of law in order to represent clients, but I would not want to be represented by a generalist on anything more than a very basic copyright issue.

There are some attorneys that specialize in copyright, or practice a lot in the area. They will have much better knowledge and advice than generalists.

2. Librarians get context

Librarians understand the structures of knowledge and information. Few copyright specialist attorneys have extensive experience with academic publishing, but academic librarians – they have an amazing view of the whole system and life-cycle of scholarly publishing. While I can’t speak as broadly about my public librarian and special librarian colleagues, I know they, too, have amazing understandings of how information, knowledge, and culture interrelate.

3. Librarians just know a lot about copyright

This fall, I did some research into what UM faculty (and lecturers and researchers) and library employees understand about copyright. The results are not scientifically rigorous (convenience-sampling, N=~50), but they do show some interesting trends.

Faculty and librarians both have a lot to learn about copyright. Across the more complex questions (usually something like “You want to make use X. Which of the following are relevant © considerations?”), both librarians and faculty got things right and wrong at similar rates. But as the table below shows, on all these complex questions, librarians were usually juuust a little more right than faculty.

|

Identification of Fair Use Considerations (results from 3 different questions) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Textual Quotation | |||

| Mean, by Role |

Correctly ID’d issues (correct positives) (out of 8) |

Incorrectly ID’d issues (false positives) (out of 2) |

Missed issues (false negatives) (out of 5) |

| Library Employees (N=23) | 3.26 | .48 | 2.96 |

| Faculty (N=28) | 2.89 | .57 | 2.93 |

| Images on Conference Slides/Posters | |||

| Mean Score, by Role |

Correctly ID’d issues (out of 9) |

Incorrectly ID’d issues (out of 1) |

Missed (out of 4) |

| Library Employees (N=21) | 3.10 | .33 | 2.52 |

| Faculty (N=27) | 2.19 | .33 | 2.96 |

|

Posting Resources to Course Websites |

|||

| Mean Score, by Role |

Correctly ID’d issues (out of 8) |

Incorrectly ID’d issues (out of 2) |

Missed issues (out of 4) |

| Library Employees (N=20) | 3.40 | .75 | 2.50 |

| Faculty (N=29) | 3.24 | .52 | 2.59 |

More importantly, on non-complex questions, such as how a copyright comes into existence, how long it lasts, and what happens when you transfer your copyrights to a publisher, library employees blew faculty out of the water

There’s an old(er) piece of web content (dating back to 1997) entitled “Why you should fall to your knees and worship a librarian” Worship is a little stronger than what I’m advocating for here, and I’m not suggesting that librarians are the only or best source of information about copyright. But I am strongly suggesting that if a librarian has information to share with you about copyright, you might want to listen pretty closely.

ETA, 2/8/11: I’m not suggesting that librarians can provide formal legal advice about copyright issues, nor that all library workers do (or should) understand copyright inside and out. I am simply suggesting that someone who works in a library who tells you that they have copyright information to share is probably significantly better-informed than most non-lawyers, and probably has solid, relevant information. I am also suggesting that it is almost always a good idea to talk with a specialist attorney for actual legal advice about copyright, since it is a specialized area of law.

This post is my just-under-the-wire contribution to Library Day in the Life Project, Round 6 It’s not quite in the standard order of the project, which is to show what a librarian’s workday is actually like, but I’d like to think it fits the spirit of the project, which is to break up stereotypes about what librarians do and know.

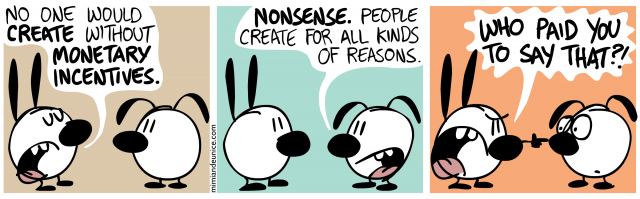

Mimi & Eunice are by Nina Paley. She says ♡ Copying is an act of love. Please copy.

I agree that monetary incentives drive the creation of lots of content. I’ll even admit that many works that are created solely due to profit motives are good! But the incentive story of copyright is a pretty limited, and limiting, view of human creativity. People create for so very many reasons – just for fun, out of love, venting rage, from passionate faith, exerting persuasion or control, expanding knowledge, for the sheer joy of creation – for all of these reasons at once, and many more besides.

The mid-modern rhetoric of copyright – where the economic incentive language really took off – used to be largely implemented around, and in reference to, the works that were created primarily for the profit motive in the first place. But the expansion of the rights claimed by economically-incentivized owners has meant that the same rhetoric is increasingly invoked as universal. That’s a problem for pretty much every public interest issue in copyright – if everyone buys the story that creation and expression are truly driven by compensation, it becomes easier to argue that all those users ought to be paying for the things they use. After all, if they didn’t pay, the things they’re using wouldn’t exist! And if they’re creating themselves, they’re only doing it to get compensated themselves!

Another note in this same tune is the argument that even if there are people who create for noneconomic reasons, their activities, while nice/pretty/admirable, are not as valuable because they don’t create much in the way of economic good to society. I don’t like to contribute to the “everything is economics” view of the world that prevails in a lot of legal discussion these days, but if ya’ll insist, I’d just add: the existing system of expansive, automatic protection for all works is a LARGE PART of the reason that many of these works don’t create much in the way of economic value.

Say an author finds a vacation snapshot in a shoebox somewhere that’s the perfect illustration to her article on mid-20th century automobile culture in the U.S. Most publishers today would not let her use the photo in a book, for fear that someday, somewhere, the unidentified photographer who took that photo is going to surface and sue – for industrial-sized damages. And yet getting paid (or launching a decades-later copyright lawsuit) was unquestionably never on the mind of the photographer who clicked that shutter. By contrast, the contributors of all the illustrations in this post – many of whom also did not have compensation on their minds at the time of creation – having taken the extra step of Creative-Commons-licensing their works, have made them available for us all to use. Which creates value for us all (assuming, of course, that my blog has some value for us all…)

So much happens in the world of creative and expressive works that is not about compensation – we need to remember that, and push back on rhetoric that normalizes and universalizes industrial modes of creative production and sharing.